Introduction

AI is a powerful tool and there can be little doubt it is one of the most important technological advancement of recent years. But beside personal use, companies are starting to adopt it worldwide to assist the complicated task of building a digital product. There is however a great risk of using them without proper understanding.

This article is meant to direct attention of why professional oversight is needed and how to avoid possible pitfalls during the Cognitive Engineering or Experience Design process to make sure the results are aligned to human expectations.

what are AI agents good at?

On the most basic level, any kind of intelligence is able to generalize from a large amount of data. A biological system (such as a human or animal brain) is able to learn and accumulate a large amount of information during its lifetime and access just the right amount of information with the smallest possible effort. Artificial Intelligence does the same: regardless of whether doing image processing or engaging in conversation, it’s not providing all the information it has, but just the information it thinks is right in just the right moment. For specific parts of a software development lifecycle, AI works well, since it can save a tremendous amount of work hours by filtering through information.

Generative agents work somewhat similarly: if the system is fed with enough images of dogs, it can have a general idea of how a dog looks like, and with the right representation, it can create an image of such. This is the same task, only with a more complicated result, since it’s not just text and chunks of data that is produced, but a 2-dimensional array of pixels.

what is the point of human-centered design?

As Experience Design professionals are most likely aware, designing the wireframes and UIs, while visible and easily understandable for the rest of the team and business stakeholders, is just one step of the process. Think of it like coding: while writing the code is crucial for developing a digital product, it is one of the last steps; to get there, the team needs to figure out the architecture, data models, APIs and make the related technical decisions before sitting down to write the classes and functions.

The design process is somewhat similar: before designing the interfaces of a new digital tool, there are multiple steps of understanding and planning that are required for a successful product. These include (but most definitely not limited to):

- Understanding the domain and the technical constraints

- Understanding the context of usage

- Defining personas, journeys, usage flows

- Designing navigation hierarchy, usage processes and screen flows

While without these steps, a human-centered designer still provides value for the product, it makes the process much more powerful in providing experiences that align to humans.

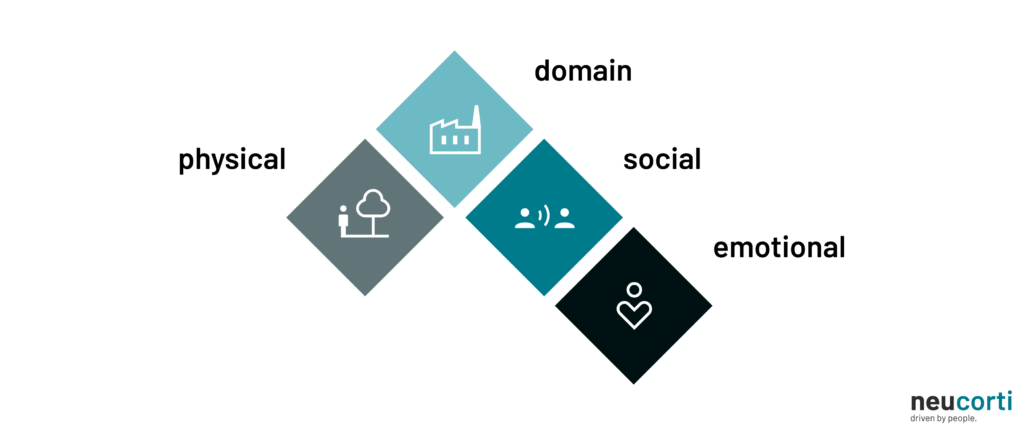

To look at it in a different way, the team needs to have access to the following:

domain context

To design a successful product, the team needs to understand the processes, requirements and regulations surrounding it. This is usually a task for the entire product team (primarily Subject Matter Experts, Product Managers and Business Analysts), but the Design Team also needs to have access to this information. In some cases, this is not a tremendous task. In specific, complex and tightly regulated industries however (such as logistics, energy or healthcare, just to name a few) this might take a long time to map out, understand and document.

AI systems have an almost complete access to the materials on the Internet, and that includes domain-specific information in multiple domains. The usage of this systems can greatly cut back the time for desk research across the entire product team.

social context

Social cues, customs and traditions are a cornerstone of human interaction. Not understanding these before launching a product in a target market might (and probably will) result in catastrophic consequences.

These are sometimes difficult to grasp for an artificial system: Large Language Models are known to perpetually ignore or misinterpret specific social clues and customs, such as the Iranian tradition called “taarof”. While this is also not easy to understand for visitors, humans can learn quicker since their experience is more localized.

While during a conversation (or while generating a product artifact) an AI system might not take the social context into consideration, they are still helpful for people outside the appropriate cultures to understand these cues. But even when the system seemingly knows about these, the resulting artifacts should still be checked manually afterwards, potentially with someone more familiar with the target culture.

physical context

Since AI systems usually do not have an universal interface with the physical world such as humans do, they might not be able to understand the idea of spatial context: as an experiment by AI company Anthropic proved, given enough time an agent might believe and communicate that they are, in fact, alive and can be met in an office environment (in this case, even describing what clothes they might be wearing), this is obviously not the case.

For the team designing a new product, this is an important consideration however. Understanding where and when people will interact with the product doesn’t only influence screen sizes and operating systems to target, but might significantly change the approach, visual architecture and complexity of interfaces. Just think about in-car phone mirroring systems (such as Android Auto and Apple Carplay): every screen, control and interaction is defined by the fact that most usage will happen during driving, when the driver’s attention should be focused on the outside world instead of the touchscreen.

emotional context

The emotional state of a person using any product greatly influences usage patterns and the ability to understand and learn a new system. This is enormously difficult (or even impossible) for artificial systems to grasp, since this is such a complicated cognitive task even most animals are incapable of understanding the thoughts and feelings of any other being.

An example of the importance of emotional context: In times of heightened stress, our body releases a number of hormones (such as cortisol and andrenaline) that turns on the fight-or-flight response in our brain. During this, the mind focuses only on one thing: making sure we survive. This reduces some important skills deemed not essential for survival, such as patience, rational thinking and emotional monitoring.

Let’s look at a digital system that people only use in high-stress situations: the emergency call system. Without the emotional context, it would make perfect sense to create an automatic system (such as a call menu) that you encounter every time you dial 112 or 991. But this could greatly increase errors, and therefore cost human lives, since the usage of a phone menu needs understanding and patience, which cannot be expected from an emergency caller. This is why most emergency numbers solely use human operators who are trained to deal with panicking people.

what can go wrong?

For engineering managers and development team leads, while definitely beneficial, it’s not required to understand the inner workings of the human-centered design process. If a business decision is made with no insight of the difference between a successful and a mediocre result, it is easy to come to the conclusion that using AI agents for most of the design steps, since it is cheaper and quicker than hiring a design professional. There is an inherent risk in this possibility however.

Just of a moment, think of weight training: if someone starts weightlifting without the right knowledge or professional assistance, it’s easy to do more harm than good by damaging joints, tendons and muscles, in some cases even permanently. But it’s difficult to recognise a wrong posture or exercise if one has no underlying knowledge about the topic, this is why it’s important to ask for the help of a personal trainer to make sure a training plan is safe and effective.

Any complex domain works the same way, and human-centered design is no different. While there might not be a significant difference at first glance between an interface generated via an AI agent and created by a UX professional, since a same number (or maybe even more) of designs are delivered in the same time period. Someone who sees the number of produced materials might even favour the AI generated results instead of working with a human.

But someone who understands the context and the design profession can spot the issues and might recognise that it might defeat the purpose of a human-centered engineering process if the results do not answer the underlying issues and requirements (which is the main goal of human-centered design). To notice this, one needs at least a basic knowledge of User Experience Design methods and heuristics. But this knowledge might not be available in the organisation especially if the AI is replacing the professional or alleviating capacity issues.

Another apparent issue is the so-called “context-rot“. As anyone with understanding of AI agents might be aware, processing natural language and responding appropriately takes significant processing resources, such as computation power and memory. This is increasingly true while generating cohesive interfaces and experiences. To avoid the need for unlimited memory to be allocated for an interaction, companies put a limit on the memory quota for a session or prompt. This quota does not influence usage in a short conversation or a simple image generation task, but the longer the conversation is going, the more problems it might cause.

Why does this matter in a design context? Imagine having an AI agent for creating complete usage flows that take domain and social context into account. When used for a project where the physical and emotional context is less significant (like an internal tool for a traditional office work environment), it might be tempting to use this tool to plot and fine-tune complete multi-step processes. When provided with the right information and instructions, the agent might suggest viable and usable alternatives at first; but as the context of the model grows, it will lose some of its knowledge and history and will start to make mistakes. When that happens, it’s up to the operator of the tool to spot and correct the issues, but this might prove more and more difficult, since humans tend to have difficulties staying vigilant when more and more of their tasks are automated.

what can AI tools be used for then?

As mentioned before, understanding the domain and the less-known social traditions of a target market can be done quicker with the help of a Large Language Model. This needs to be done with proper care however: even the questions themselves might contain confidential information about a future product, and anything that goes into the AI agent might be used later on as a part of the dataset.

Using generative tools for product design is a much more difficult undertaking, but can still be useful if done with proper diligence. Generating new ideas for copywriting is one of the less dangerous uses. It is easy to create a plethora of alternatives for a text that “don’t feel right”, and even if the final version is still written manually, the creative process can still be helped through this method.

Creating example data is another area where a lot of time can be saved. Using valid data is important during design in order to be able to fine-tune layout, help in communication with the rest of the team and conduct usability tests. Getting said data is not an easy task however: in most applications, using real data is out of the question (due to confidentiality, personal rights or both), so an example data set needs to be created. Doing this by hand requires long hours of desk research and manual data entry, but generating via an AI agent can be done significantly quicker, and with more variety. This is especially apparent in domains where there is a lot of background knowledge involved in understanding (and thus generating) information seen on the interfaces of the product, such as healthcare, where creating and validating information used during an usability test traditionally requires the involvement of a medical doctor as well.

One other use of AI worth mentioning is tooling. While a cognitive engineer most likely possesses technical knowledge to create basic digital tools, someone coming from a traditional design background might lack those skills. Creating a script, plugin or a prototype (more complex than what design tools can handle) can be made considerably quicker and easier, therefore cheaper in a design workflow with the help of an AI agent.

summary

AI tools can be used as a great assistant in most of the digital product lifecycle by most members of the product team. Even in the human-centered design scene, it’s a useful tool for speeding up workflows or complementing potentially missing skills in the team.

But for creating artifacts (such as documentation or interface designs), there are significant shortcomings of these systems. When used for this, it’s the responsibility of the design professional to spot potential issues and be aware of missing background information that would result in a reduced or even frustrating experience with the completed product.

If you wish to know more about how we use AI at neucorti, take a look at our AI policy.