want to get to the point?

If you wish to skip the intro and get straight to the details, start reading at basic principles.

what is cognitive engineering?

Cognitive Engineering is a different approach to designing digital products by using an engineering approach. The pillars of this approach is formalized processes, repeatability and measurability. While the rest of the software engineering professionals (such as development, DevOps and product management) do have these processes lined out and being used, the product design community does not have access to the same selection of tuned processes to choose from. Cognitive Engineering wishes to give an option for these professionals to have a predefined method of designing and validating all touch points between computer and human.

how does this differ from User Experience Design?

User Experience (UX) Design is the accepted terminology for designing human-computer interaction. Then, one might ask, what is the point of using a new terminology for the same discipline?

There are multiple flaws with the term “User Experience Design”:

- The word “User” is often used in a pejorative way: while, without doubt it refers to people using a product, most of the time it’s strengthening the separation between the “us” and the “users”, therefore hindering the collaboration between product teams and customers. This is the reason product design professionals are using personas instead of categorizing customers into predefined categories.

- “Design” refers to a process of “deciding upon the look and functioning of (a building, garment, or other object), by making a detailed drawing of it” (Oxford Dictionary), which is, in itself can refer to a professional creating digital interfaces for a product. In the highly competitive and technical field of software engineering however, it’s easy to associate the word with art and aesthetics, which (as practicing UX professionals would likely agree) does not cover the often highly technical process of devising an intuitive human-computer interface.

Even if we try to disregard the negative psychological aspects of the naming of this profession, UX Design is only a part of the entire Cognitive Engineering toolchain. While creating interfaces is an important part of the process, there are equally important steps that might or might not be a part of a UX Design process, such as analysis of business processes, research (both desk and field research), deciding on measure points, documenting and validating usage patterns with quantifiable tests.

why should I care?

It might seem like this is a step back into the pre-Agile ways of Software Engineering, where the main task of a developer were to create the right amount of documentation that no one ever reads.

The methods, processes and templates outlined in this website should be fine-tuned to each team’s personal preference and needs; most sections of an interface documentation for example might be a waste of time for a one- or two-person design team, but might be imperative for a product team with over 10 designers to ensure timely communication and the ability to avoid single points of failure for the team. As a decision maker or independent professional in the human-computer interaction field, this approach does have some major positives however, such as:

- more design decisions based on scientific evidence rather than industry best practices

- an ability to establish a single source of truth about a project

- easier onboarding for new team members

- repeatable and auditable processes

- quantifiable usability, therefore easier communication with stakeholders, clients and other team members

This approach is not a silver bullet for all product engineering woes, so in order to get these benefits, it needs constant effort from the team members, which does take more dedication and discipline than just handing off interface wireframes to the development team on a meeting; if your team’s goal is to create as much content as possible in the shortest amount of time (for example if working on short lifecycle or disposable digital products), this trade-off might not be worth it.

If, however, the products your team is working on products that have longer lifecycles, teams with a high turnover rate or a possibility to scale up perpetually, the extra effort needed for this approach is well worth it.

basic principles

Getting started with Cognitive Engineering is not a huge effort, especially if one is already working as a UX Designer or Researcher, since most of the principles are the same. For UX Designers, the primary effort is mostly a mindset shift.

UX Design is still associated with art and aesthetics, this is especially frequent with higher level decision makers. While those working in the industry know the work is more related to psychology, our current methods do not help disprove this idea. Quite a few of our design decisions are based on industry best practices and gut feelings, which, even if they are completely right, do not strengthen the look of a well established profession based on facts and measurable information.

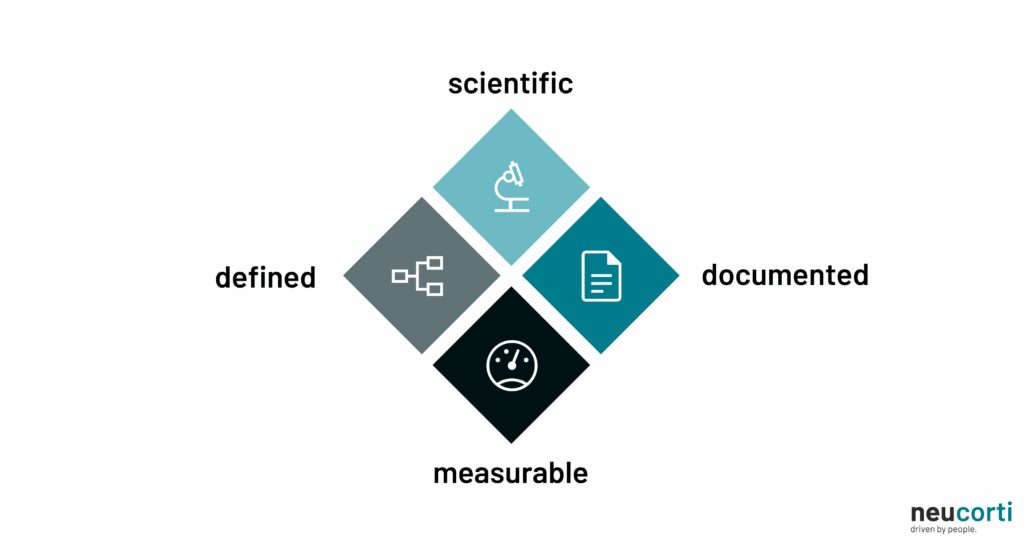

As part of an engineering team (where every decision has a scientifically proven rationale behind it), this does not put the designers in a good light. Cognitive Engineering tries to solve this by outlining a few basic principles that help the UX Design community have the same kind of reasonableness as the rest of the disciplines in a project team.

scientific basis

While best practices are an easy way to make our decisions and make our work more effective, they often lack reasoning based on scientific principles. While using an engineering approach, this issue is solved with an underlying knowledge in Cognitive Sciences that can make us prove (or disprove) our industry best practices.

This also gives us an edge in communicating our decisions, since the best practices themselves don’t give stakeholders and decision makers trust in said decisions other than “this is how we have always done things”.

extensive documentation

Quite a few design projects lack documentation other than the interface designs themselves, and this places further strain on the collaboration between the designer and the developer; since the design process should support the development process, not slow it down, all artifacts should follow a form factor the development team is comfortable in. Since software engineering is a highly formalized discipline, most developers navigate more intuitively in text-based media than canvas-based information such as the pages of a design tool.

defined process

Often when a design team is asked about their processes, we describe a high-level overview (such as the cycle of design thinking or the Double Diamond). While these are valuable tools of communicating the approach and mindset of designers, but compared to the rest of the development lifecycle it’s way too high-level to be able to give decision makers the ability to plan and audit the steps of the design process.

A different approach would be to outline an iterative, low level design process that helps the entire project team understand the way of producing design artifacts. Think of it like the steps of a code review, but about design tasks. Most teams have their own version of this, but there is no industry-wide conclusion of what these might be.

measurable usability

The design profession prefers qualitative results rather than quantitative research: this is what usability testing is all about. This helps us understand our customer group more deeply, but they don’t say much to engineering decision makers who need straightforward quantitative information to decide the project’s next steps. This is why next to qualitative research (but definitely not instead!) the design process should result in understandable and quantifiable KPIs that can be communicated to higher-ups to prove the added value.

This might take the form of already existing frameworks (such as the System Usability Scale or the NASA Task Load Index), or improving the usability testing process with eye tracking, pupillometry or EEG data.

next steps

Following these guidelines might look complex at first: UX Design professionals might not have the experience or the willingness to change their workflow into a more formal process, after all this part of the product lifecycle was always about the free flowing ideas and breaking the mold; but after a mindset shift, at the price of the small extra effort of measurement and documentation, the design community instead of the perception of only slowing down the software lifecycle, can be esteemed members of development teams and an integral and essential part of the development of any digital product.

table of contents